Food Processing Unit Operations Quiz

1. What is the primary purpose of "Cleaning and Sorting" in food processing?

2. Which unit operation is used when turning wheat into flour?

3. What is the key difference between unit operations and unit processes?

4. Which method would be used to separate fat from milk?

5. What is the primary purpose of "Drying and Dehydration" in food processing?

6. Which of these is an example of a unit operation?

7. What is the most critical unit operation for food safety according to the article?

Quiz Results

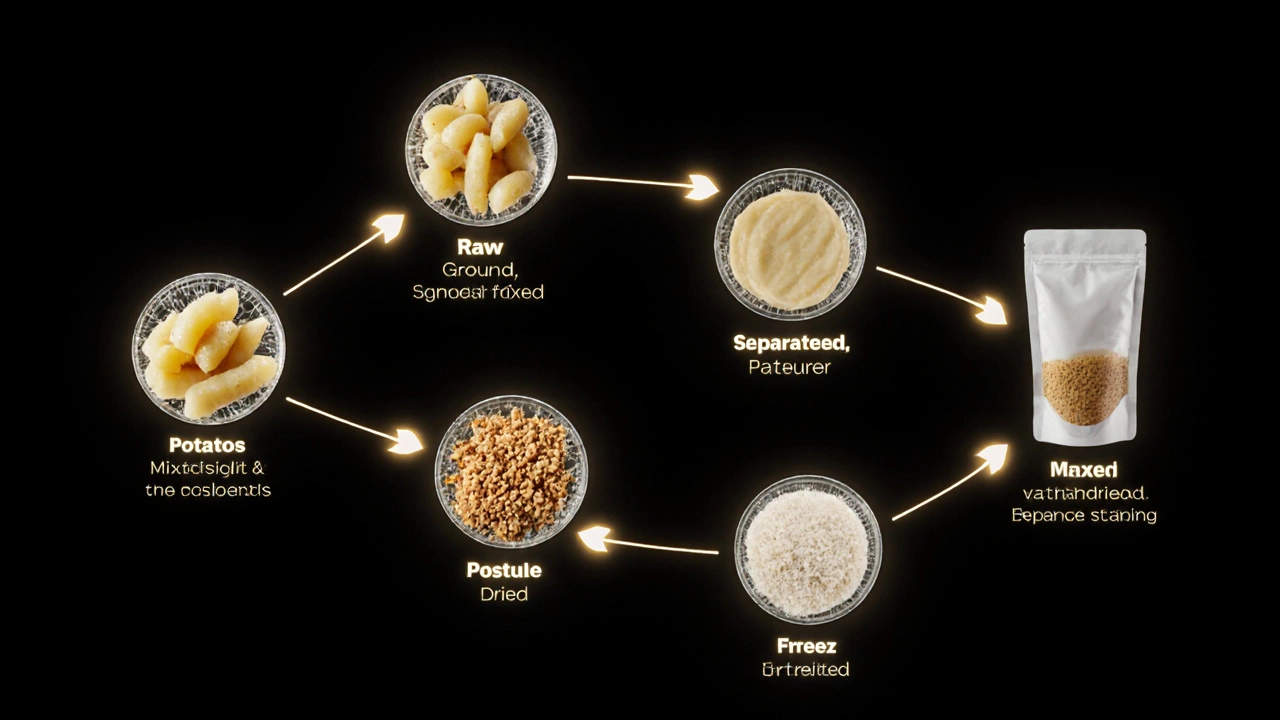

Score: 0/7Ever wonder how raw milk turns into yogurt, or how apples become apple sauce? It’s not magic-it’s food processing. Behind every packaged food you buy, there’s a series of simple, repeatable steps called unit operations. These aren’t fancy robots or AI systems. They’re the basic physical and mechanical tasks that change food from raw to ready-to-eat. Think of them like the building blocks of everything from canned soup to frozen pizza.

What Exactly Are Unit Operations?

Unit operations are the individual steps in food processing that involve physical changes, not chemical reactions. That means no cooking or fermenting here-those fall under unit processes. Unit operations are about moving, separating, mixing, heating, or cooling food. They’re the same whether you’re making jam in a small kitchen or peanut butter in a factory.

These steps are standardized across the industry. A dairy plant in India and a juice factory in Germany both use the same core unit operations. That’s why food safety and quality control are so consistent worldwide. The goal? To make food safe, shelf-stable, and pleasant to eat-without losing its nutrition or taste.

1. Cleaning and Sorting

It sounds simple, but it’s the most critical first step. Raw ingredients come straight from farms, fields, or fisheries. They carry dirt, insects, stones, leaves, and sometimes even metal fragments. Before anything else happens, food must be cleaned and sorted.

For fruits and vegetables, this means water sprays, brushes, and air blowers. Potatoes go through vibrating screens to remove dirt. Grains pass over magnets to pull out nails or screws. In meat plants, carcasses are washed with food-grade sanitizers. Sorting might be manual-like picking out bad apples-or automated with cameras and AI that spot discolored or damaged items.

Skipping this step risks contamination. A single piece of metal in a cereal box can cause serious harm. That’s why cleaning and sorting aren’t optional-they’re legally required in most countries.

2. Size Reduction

Ever notice how tomato paste is smooth but whole tomatoes are chunky? That’s size reduction at work. This step breaks down food into smaller pieces using cutting, grinding, chopping, or milling.

For example:

- Wheat is milled into flour using roller mills.

- Meat is ground into mince with a meat grinder.

- Spices are pulverized into powder using hammer mills.

The goal isn’t just texture. Smaller pieces heat and cool faster, mix more evenly, and preserve better. A chunky sauce takes longer to pasteurize than a smooth one. That’s why size reduction often comes before heating or sterilization.

Equipment varies by scale. Small producers use hand grinders. Large plants use high-speed disc mills that process tons per hour. The key is controlling particle size-too fine, and you lose mouthfeel; too coarse, and you risk uneven processing.

3. Mixing and Blending

Think of baking a cake. Flour, sugar, eggs-each ingredient needs to be evenly distributed. That’s mixing. In food processing, it’s the same, just on a much larger scale.

Mixing isn’t just for recipes. It’s how you add vitamins to breakfast cereal, salt to bread dough, or flavorings to yogurt. Poor mixing leads to inconsistent products-some packets too salty, others bland.

Equipment includes ribbon blenders for dry powders, paddle mixers for thick pastes, and high-shear mixers for emulsions like mayonnaise. The trick is matching the mixer to the material. You wouldn’t use a blender meant for liquids to mix flour and sugar-it would just create a dust storm.

Modern plants use sensors to monitor mix uniformity in real time. If the blend isn’t right, the system alerts operators before the batch goes further.

4. Separation

Not everything in food is useful. Skim milk isn’t just a trend-it’s the result of separation. Fat is removed from milk using centrifuges. Juice is clarified by filtering out pulp. Oil is pressed from seeds and then separated from water.

Common separation methods:

- Centrifugation: Spins food at high speed to separate components by density. Used in dairy, oil extraction, and wine clarification.

- Filtration: Passes liquid through mesh or membranes to remove solids. Think coffee filters, but industrial-sized.

- Settling: Lets heavier particles sink naturally. Used in fruit juice production to let pulp drop to the bottom.

- Screening: Uses mesh screens to sort by size. Removes seeds from purees or husks from grains.

Separation isn’t just about removing waste. It’s also about concentrating what you want. For example, evaporating water from fruit juice to make concentrate saves space and energy during shipping.

5. Heating and Cooling

Heat and cold are two of the most powerful tools in food processing. They kill harmful bacteria, extend shelf life, and change texture.

Heating methods:

- Pasteurization: Heats food to 60-85°C for a short time. Kills pathogens without cooking the food. Used for milk, juice, and eggs.

- Sterilization: Heats to 121°C under pressure. Used for canned goods like beans or soups. Kills all microbes, including spores.

- Blanching: Briefly dips vegetables in boiling water before freezing. Stops enzyme activity that causes spoilage.

Cooling methods:

- Refrigeration: Keeps food at 0-4°C. Used for fresh produce, dairy, and ready meals.

- Freezing: Cools food to -18°C or lower. Slows microbial growth almost to a stop. Used for frozen vegetables, meats, and desserts.

- Evaporative cooling: Uses air flow to remove moisture and lower temperature. Common in drying fruits or cooling baked goods.

Timing matters. Overheat milk, and it turns into scalded custard. Underfreeze meat, and ice crystals ruin the texture. Precise control is everything.

6. Drying and Dehydration

Water is the enemy of long-term food storage. Bacteria, mold, and yeast need it to grow. Remove the water, and food lasts for months-or years.

Drying methods:

- Sun drying: Traditional, low-cost. Used for raisins, tomatoes, and chilies in warm climates.

- Drum drying: Spreads liquid food on heated drums. Used for milk powder and instant potato flakes.

- Spray drying: Turns liquid into fine mist and dries it with hot air. Used for powdered milk, coffee, and broth.

- Freeze drying: Freezes food, then removes ice by sublimation. Used for instant coffee, astronaut meals, and premium fruit snacks. Preserves flavor and nutrients better than heat drying.

Dried foods are lighter, cheaper to ship, and don’t need refrigeration. That’s why instant noodles, powdered soups, and snack bars rely on this step.

7. Packaging

Processing isn’t done until the food is sealed. Packaging protects food from air, moisture, light, and germs. It also keeps it fresh, safe, and appealing.

Common packaging types:

- Vacuum sealing: Removes air to prevent oxidation. Used for cheeses, meats, and nuts.

- Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP): Replaces air with nitrogen or CO2. Keeps salads crisp and meats red.

- Retort pouches: Flexible, heat-resistant pouches for ready-to-eat meals. Lighter than cans, easier to open.

- Blister packs: Plastic shells with foil backing. Used for single-serve snacks or supplements.

Modern packaging includes smart labels that change color if the food spoils. Some even track temperature history to ensure safety during transport.

Why These Steps Matter

These seven unit operations aren’t just technical steps-they’re the reason your food doesn’t make you sick. They’re why you can buy frozen peas in winter, drink pasteurized milk without boiling it, or eat dried fruit on a hike.

Each step is designed with science, safety, and efficiency in mind. They’re repeated daily in thousands of factories worldwide. And while automation has made them faster, the core principles haven’t changed in 100 years.

Understanding them helps you read labels, choose better products, and even start your own small food business. You don’t need a PhD to know what’s in your food-just a grasp of these basic steps.

Are unit operations the same as unit processes?

No. Unit operations involve physical changes-like cutting, mixing, or heating. Unit processes involve chemical or biological changes, like fermentation, pasteurization (which is sometimes classified as a process), or enzymatic reactions. For example, turning milk into yogurt using bacteria is a unit process. Separating the cream from milk is a unit operation.

Can small businesses use unit operations too?

Absolutely. A home jam maker uses cleaning (washing fruit), size reduction (chopping), mixing (adding sugar), heating (boiling), and packaging (jarring). The tools are smaller, but the principles are identical. Many artisanal food producers rely on the same unit operations as big brands-they just scale them down.

Which unit operation is most important for food safety?

Cleaning and sorting come first, but heating (pasteurization or sterilization) is the most critical for killing pathogens. Without proper heat treatment, harmful bacteria like E. coli or Listeria can survive and cause outbreaks. That’s why food safety inspectors focus heavily on time-temperature logs during these steps.

Do all foods go through all seven unit operations?

No. A bag of raw rice only needs cleaning and packaging. Frozen strawberries might skip drying and go straight from cleaning to freezing. The steps used depend entirely on the final product. A loaf of bread uses mixing, heating (baking), and packaging-but no separation or drying.

How do unit operations affect nutrition?

Some steps can reduce nutrients. High heat during pasteurization can lower vitamin C in juice. Drying can destroy heat-sensitive compounds. But many operations preserve nutrition-like freezing, which locks in nutrients better than canning. The key is balancing safety with nutrient retention. Modern processing often uses gentle methods like cold pasteurization or vacuum drying to minimize loss.

What Comes Next?

If you’re curious about how these steps are controlled in real factories, look into automation systems like PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers). They monitor temperature, speed, and flow rates to keep every batch consistent. Or explore how food scientists design new products by tweaking just one unit operation-like using high-pressure processing instead of heat to kill bacteria.

Understanding these basics opens the door to everything else-from reading food labels to starting your own small-scale food business. You don’t need to be an engineer. You just need to know what happens between the farm and your fridge.