Textile Industry Cost Comparison Calculator

How India Compares to Other Countries

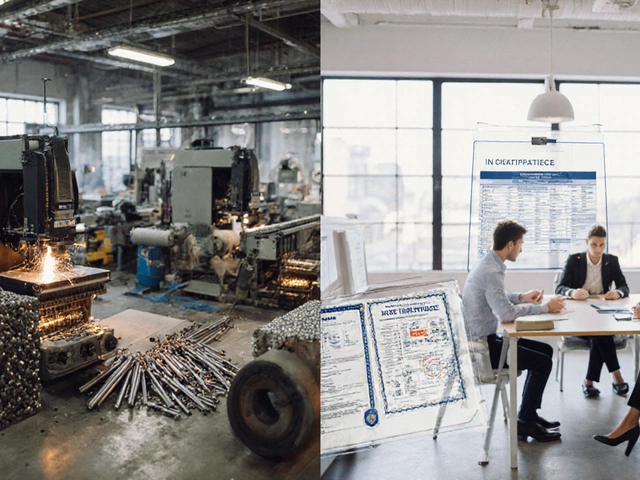

Compare key manufacturing factors that impact competitiveness in the textile industry. Input values based on your knowledge of industry data to see the competitive differences between India and major textile producers.

Competitiveness Analysis

Bangladesh is 0% more cost-efficient than India for this scenario

Bangladesh produces 0% more fabric per hour than India

India used to be the world’s largest producer of cotton textiles. In the 1980s, it supplied nearly 20% of global cotton fabric exports. Today, that number is under 5%. Factories that once hummed with the sound of looms now sit silent. Why? The decline isn’t one big mistake-it’s a chain of failures that started decades ago and kept getting worse.

Global competition crushed local prices

China didn’t just outproduce India-it outpriced it. By the early 2000s, Chinese mills were making the same cotton fabric at 30% less cost. How? They had government-backed subsidies, state-owned energy at rock-bottom rates, and massive scale. Indian manufacturers, mostly small and family-run, couldn’t compete. A single Chinese factory could produce in one week what 20 Indian units did in the same time. Buyers in the U.S. and Europe switched. Why pay more for slower delivery when the quality was nearly identical?

India’s tariffs on imported yarn and fabric were too low to protect domestic producers. Meanwhile, China slapped high duties on Indian cotton exports. The playing field wasn’t just tilted-it was flipped.

Outdated machinery and slow tech adoption

Walk into a textile mill in Tiruppur or Surat today, and you’ll likely see machines from the 1970s. Many still use ring spinning, which is slower and uses more labor than modern open-end spinning. The average age of looms in India is over 25 years. Compare that to Bangladesh, where new automatic looms arrived in bulk after 2015, cutting production time by 40%.

Indian manufacturers didn’t upgrade because financing was hard to get. Banks saw textiles as a dying sector. Equipment loans had 14% interest rates, while China offered 3% for modernization. Even when money was available, owners didn’t trust new tech. They feared downtime, training costs, and workers who couldn’t adapt. So they stuck with old machines-until they broke down for good.

Labor costs rose, but productivity didn’t

Wages in India’s textile sector have doubled since 2010. But output per worker? It barely moved. In Bangladesh, one worker produces 12 meters of fabric per shift. In India, it’s 7. Why? Poor training. No standard operating procedures. Machines left idle because no one knew how to fix them.

India has millions of textile workers, but almost none are formally trained. A 2023 survey by the National Council for Applied Economic Research found that 82% of textile workers had no certification. In contrast, Vietnam’s government runs mandatory textile skill programs funded by export taxes. Indian workers learned on the job-if they were lucky.

Supply chain chaos

Getting cotton from farm to factory in India is like solving a puzzle with half the pieces missing. Farmers sell to middlemen, who sell to traders, who sell to spinning mills. Each step adds cost and delay. By the time cotton reaches the loom, it’s 20% more expensive than in Uzbekistan or the U.S., where supply chains are direct.

Power cuts are still common in rural textile hubs. A mill in Maharashtra might lose 12 hours of production a month just from blackouts. In Turkey or Egypt, factories run on uninterrupted grid power. Even when electricity is stable, logistics are a mess. A container of finished fabric might take 10 days to reach the port because of local transport bottlenecks. In Bangladesh, it takes 3.

Design and branding lag behind

India makes great fabric. But who buys Indian fabric? Mostly other countries that rebrand it as “Made in Italy” or “Designed in Paris.” Indian mills rarely build their own labels. There’s almost no investment in fashion design, marketing, or retail.

Compare this to Turkey. Turkish textile companies spend 5% of their revenue on design teams and global branding. They sell directly to Zara, H&M, and Uniqlo under their own names. Indian companies? They’re stuck as anonymous suppliers. A single Indian exporter told me they shipped 2 million meters of fabric to Spain last year-and never once saw the final product on a store shelf.

Policy gaps and inconsistent support

India has launched over 15 textile schemes since 2010. The Technology Upgradation Fund Scheme. The Amended Technology Upgradation Fund Scheme. The Production Linked Incentive Scheme. Each sounds good on paper. But implementation? Patchy.

Companies that applied for subsidies in 2021 are still waiting for payments. Some got only 30% of what they were promised. The rules change every year. A factory that qualified for funding in 2022 might not in 2025. No one knows what’s coming next. That kind of uncertainty kills investment.

Meanwhile, countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh have one clear policy: export more, get more help. They tie subsidies directly to export volume. Indian policy is scattered-focused on jobs, not growth. And it rarely listens to the people running the mills.

Environmental rules hit small players hardest

India’s new environmental norms for textile dyeing and wastewater treatment are strict-and expensive. A small mill needs ₹2-3 crore to install a zero-liquid discharge system. That’s more than the entire annual revenue of many units.

Big players like Arvind Limited can afford it. But 90% of India’s textile units are small. Many just shut down instead. Others dump waste illegally. Enforcement is weak, but the threat is real. So instead of upgrading, they close. And with them go thousands of jobs.

What’s left? And what can be done?

It’s not all doom. India still has strengths. It grows the most cotton in the world. It has skilled handloom weavers in Varanasi and Kanchipuram. It has a young population ready to learn. But these aren’t enough.

Reversing the decline needs three things: First, massive investment in modern machinery-with real subsidies, not promises. Second, a national training program that certifies every textile worker. Third, a single, stable policy that rewards exports, not paperwork.

Without that, India won’t just lose market share. It will lose its identity. Textiles aren’t just fabric. They’re heritage. They’re millions of hands that built the economy. Letting them fade isn’t just an economic failure-it’s a cultural one.

Is the Indian textile industry still big?

Yes, but not like before. India is still the second-largest textile producer in the world after China, and it employs over 45 million people. But its share of global textile exports has dropped from 6% in 2010 to just 3.8% in 2025. It’s big in volume, but shrinking in value and competitiveness.

Why can’t India compete with Bangladesh?

Bangladesh won because it focused on one thing: making garments fast and cheap. It invested in automated machinery, trained workers through government programs, and built reliable logistics. India tried to do everything-handlooms, powerlooms, exports, domestic brands-and ended up doing none of them well. Bangladesh also got preferential trade access from the EU and U.S. India didn’t.

Do Indian textile manufacturers still export?

Yes, but less than before. In 2024, India exported $13.5 billion in textiles and apparel. That’s down from $15.2 billion in 2021. Major buyers are the U.S., UAE, and UK. But India now supplies only 2% of U.S. apparel imports-down from 4% in 2015. Bangladesh and Vietnam now supply more.

Are handlooms dying in India?

Not entirely, but they’re under pressure. Over 4 million handloom weavers still work across India, mostly in rural areas. But their income has fallen by 35% since 2018 due to cheap machine-made imitations and lack of market access. Government schemes help a little, but they don’t reach most weavers. Without better design, branding, and digital sales channels, handlooms will keep shrinking.

Can India revive its textile industry?

Yes-but only with bold, consistent action. India needs to stop treating textiles as a welfare sector and start treating it like a high-growth export engine. That means modernizing factories, training workers, fixing supply chains, and creating global brands. It also means sticking to policies for five years, not five months. The potential is there. The will isn’t.