Picture this: you’re cruising down Galle Road, the ocean is on your left, coconut trees waving you on. But as you watch the traffic, every badge flashes Toyota, Suzuki, Honda, or the odd Nissan. Ever wonder—does Sri Lanka actually produce cars, or do we just play host to imported wheels? It sounds simple, but the answer is tangled up in ambition, economics, and some wild stories you probably haven’t heard before.

The History of Car Manufacturing in Sri Lanka: Passion Meets Reality

Sri Lanka cars have a history that starts more like a dream than a business plan. The push to build cars locally took root long before the world started obsessing over electric vehicles or smart driving tech. Way back in the 1960s, the government wanted to lessen its dependence on imports, especially with the island’s persistent foreign reserve crunch. Political leaders talked about self-sufficiency, factories, and even exports. But let’s be real: mass-producing cars isn’t like churning out tea or coconuts. It’s a whole different game.

By the late ’80s and early ’90s, experiments began in government workshops and semi-private ventures. The fantasy was to give the island its own signature wheels—small, fuel-efficient, built for local roads. In the early 2000s, microcar workshops began putting together “assembled” cars with parts shipped from abroad, offering an alternative to expensive imported secondhands. But real mass production? That was always just out of reach.

Here’s one for the trivia books: the first truly Sri Lankan car to make headlines—at least domestically—was the Micro. Launched in 1999 by entrepreneur Dr. Lawrence Perera, the Micro quickly grabbed the spotlight. It was uniquely tailored for local conditions, aiming to be affordable and robust. Micro Holdings PLC grew, releasing models like the Micro Panda and small pickup trucks, developing a kind of cult following for a while. People started asking if Micro would become the country’s Toyota. The heady days faded when the brand hit snags with financing, shifting policies, and the weighty cost of automotive R&D, which often runs into billions for even established international brands.

The industry also flirted with the idea of electric tuk-tuks and small utility vehicles—a clever fit for Sri Lanka’s roads and villages. But importing crucial parts and battery technology, plus frequent policy shifts on vehicle taxes, kept these businesses from gaining real mainstream traction.

The Current Scene: What’s Rolling Out of Sri Lankan Factories?

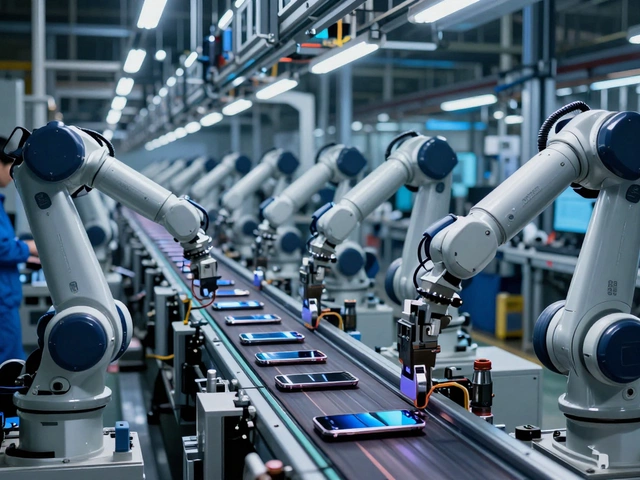

Jump to 2025 and the auto landscape is a mixed bag. There’s no massive car manufacturer churning out sedans or SUVs for the world market from Sri Lanka. Still, local car manufacturing does exist—just not in the form you might expect. The majority of vehicles hitting the road in Sri Lanka are either imported fully built or assembled locally from knocked-down kits (CKD units). What’s the difference? Assembling from CKD kits means getting all the parts shipped in from China, India, or Japan, then putting them together in local factories. Only a handful of components—like batteries, tires, or glass—might be sourced from Sri Lankan suppliers.

Micro Holdings PLC is still hanging in there, despite production stalls and tax obstacles. They’ve made compact sedans, small hatchbacks, and light trucks. Other local brands, like the Ideal Motors (which tied up with India’s Mahindra), have brought assembled vehicles like the Mahindra KUV100 NXT onto Sri Lankan roads, labeling them as locally assembled. But the engine blocks, transmissions, and chasses still come from India. The “Sri Lankan-ness” of these cars is more in the effort than in the engineering.

Then there are quirky, innovative ventures. Vega Innovations grabbed headlines in the last few years by creating the Vega EVX, South Asia’s first supercar—yep, a proper electric sports car, designed and assembled in Colombo. Its sleek body and futuristic dashboard wowed at the Geneva International Motor Show in 2020. But don’t expect to see hundreds of Vegas parked on the street—only a handful of prototypes were ever made, and serious production isn’t commercially viable yet for such a niche car.

The majority of industrial assembly happens in the commercial vehicle sector—things like three-wheelers (tuk-tuks), light trucks, and agriculture vehicles. TVS and Bajaj, both giants from India, have licensed their designs for local assembly. Sri Lankan workshops custom-build bodies for delivery trucks, ambulances, and buses using overseas frames and engines. These jobs keep thousands employed in Colombo, Gampaha, and Kandy, but they’re still far from a full-fledged automobile industry found elsewhere in Asia.

Why Mass Production Faces Major Hurdles in Sri Lanka

So why hasn’t Sri Lanka ramped up to full-on car production the way Thailand, Malaysia, or even Vietnam has? The blunt answer: scale and economics. Consider this—Thailand makes over 2 million vehicles a year, mostly for export. Sri Lanka’s car market is tiny by comparison; as of 2023, annual new vehicle registrations had dipped below 30,000 units, partly thanks to tough import restrictions and economic headwinds.

| Country | Annual Car Production |

|---|---|

| Thailand | 2 million+ |

| Vietnam | 360,000+ |

| Sri Lanka | Less than 2,000 (including CKD assembly) |

Automotive manufacturing requires huge investments in technology, factories, skilled labor, and supply chains. If you’re only making 1,000 or 2,000 cars a year, you simply can’t compete on cost or sophistication against global manufacturers. Sri Lanka’s market is largely made up of budget-minded customers looking for reliability, affordability, and fuel efficiency rather than homegrown pride.

Then there’s government policy: vehicle import taxes can swing wildly—sometimes slashed to boost the auto market, other times hiked up to save crucial foreign reserves. Investors need stability, but Sri Lanka’s economic scene has been rocky. For auto start-ups and investors, repeated policy reversals make long-term planning a huge gamble. You also have to factor in global supply chain snags, especially with crucial computer chips and high-quality steel. Sri Lanka doesn’t have domestic suppliers for those, so factories wait for shipments from China or India. Any delay throws assembly lines out of whack.

How about electric cars? There’s hope. The government has toyed with ideas for tax breaks and local assembly incentives. A few e-tuk factories are testing waters in Negombo and Moratuwa, retrofitting classic tuk-tuks with battery packs. But making electric cars at scale asks for specialized skills, batteries, and constant R&D money. Sri Lanka is in catch-up mode here, while global giants are years ahead.

The Future: Can Sri Lanka Build Its Own Car Legacy?

Will we see a true "Made in Sri Lanka" car cruising Colombo’s Marine Drive any time soon? Maybe, but it’ll take a lot more than good intentions and cool prototypes. Most experts say that, if Sri Lanka is going to carve out a niche, it’ll likely be in electric vehicles, three-wheelers, or specialized utility vehicles. Why? The island’s market isn’t big enough to rival even Malaysia’s Proton or Vietnam’s VinFast, but it could become a test bed for small-scale urban vehicles or last-mile mobility solutions—think city EVs, electric tuk-tuks, or unique compact delivery trucks optimized for narrow Sri Lankan streets.

Innovation is already happening on a small scale. Startups are experimenting with electric conversions, 3D-printed body panels, and solar-powered vehicle ideas. There’s a lot of buzz about green incentives: the government regularly floats plans for reduced taxes on EVs, free charging infrastructure, and cash grants for local assembly lines. Universities and research centers are jumping in too, offering engineering talent and lab resources, hoping to nurture a next-generation auto workforce.

If you’re thinking of buying a locally assembled Sri Lankan vehicle, here are some tips: Check the warranty and after-sales support, since many smaller brands may not have big service networks. Look for reviews on parts availability—many local assemblers face delays importing spares. And be ready for a mixed driving experience: locally assembled cars often use proven engine and chassis designs borrowed from foreign partners, which can be a good thing for reliability, but they might lack the polish or high-tech features of fully imported rivals.

- Sri Lanka’s only car entry showcased on the global stage, the Vega EVX, delivers 804 horsepower and goes from 0 to 100 km/h in 3.1 seconds—but costs over $250,000 and exists as a limited-run prototype.

- As of 2024, fewer than 50% of the auto parts in “locally made” Sri Lankan vehicles are actually sourced from local suppliers. The rest are imported.

- The average age of cars on Sri Lankan roads is over 15 years—way above the global average. Import crackdowns since 2020 have left the island holding onto old wheels a lot longer than before.

So, does Sri Lanka produce cars? The truthful answer: yes, in its own way, with small-batch local assembly, ambitious start-ups, and the occasional flash of international innovation. But if you’re picturing a vast assembly line with new sedans rolling out by the thousands, that’s still just out of reach. Maybe someday we’ll see a car that’s fully Sri Lankan in spirit and in nuts and bolts—until then, keep an eye out for Micro hatchbacks, electric tuk-tuks, and maybe a glimpse of a Vega supercar humming down the Southern Expressway.